Historical bonds

Bonds that were once valid obligations of American entities but are now worthless as securities and only collected and traded as memorabilia -- are quickly becoming a favorite tool of scam artists. Here are several things that you should know about them:

Three Lies Used to Perpetrate Historical Bond Fraud:

Lie 1 : Historical bonds are payable in gold.

Lie 2: Historical bonds are backed by the Treasury Department.

Lie 3: The Treasury Department has established a federal sinking fund to retire historical bonds.

How Scam Artists Use Bogus Third-Party Valuations to Trick Investors

Scam artists are selling historical bonds to unsophisticated investors at inflated prices far exceeding their fair value as collectibles. They often use third-party valuations, which state that the bonds are worth million or billions of dollars each, to do so. These valuations or authentications, which are often referred to as "hypothecated" or "hypothetical," are completely bogus. A typical valuation will falsely overstate the value of these bonds by assuming erroneously that, notwithstanding the unenforceability of the gold clauses contained in the bonds, as well as the defunct and bankrupt status of most of the bonds' issuers, some person or entity is obligated to redeem the bonds in gold bullion.

Scam artists using such valuations may also make the false assertion that while perhaps not payable today in gold or in money, the bonds are used in high-yield trading programs in the United States, offshore and in Europe. In several cases, the third parties issuing the valuations appear to be working in conjunction with the scam artists. All of these false assertions have been used to defraud investors into paying as much as $150,000 for historical bonds that regularly trade for $25.

Fraudulent Cash and Railroad Bond Program Operator List

Part I consists of those individuals who, through their own words and deeds, have proven themselves cons to unwary investors and have been reported to the various authorities for their Securities Violations. Part II consists of the business names through which these individual have been known to operate. Pertinent notes are sometimes annotated to clarify level of involvement in the fraud and how interconnected.

Extreme caution should be exercised in transactions that may utilize these individuals. Deception has been utilized to cover their involvement in many a transaction by hiding behind other parties. Latest is to, now more than ever, hide under a completely new "front man" and place their "Program" with parties published herein. This list is not all-inclusive and should not be viewed as such.

The author of this publication, Henry R. Wentworth, has spent years developing the database contained herein. His second publication, Bank Debentures: Names You Should Know, contains a database with a focus on the market for ‘bank Debentures.’

Forex news, currency trading news, analysis, articles, research and commentary. Forex News Trader can provide you with tools to help increase your trading performance over the long run.

Sunday, June 6, 2010

Warning from the IMF against financial schemes misusing its name

In view of widespread and continuing inquiries from individuals and companies who have been approached by parties in connection with offers of participation in various financial instruments and schemes promising high returns and unauthorizedly using the name of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the Treasurer of the IMF today again warned potential investors to beware of such schemes. He had already issued warnings in the past (see News Brief Number 94/5, published February 23, 1994 and News Brief Number 94/11, published May 13, 1994). Today he reiterated that the IMF does not issue or guarantee any obligations called "Prime Bank Notes," "Prime Bank Guarantees," "Bill of Exchange," or "Bill of Equity," or extend any credit lines through commercial banks or other agencies. Moreover, the IMF does not guarantee debentures or other financial instruments issued by a member country or any other entity. It does not sponsor investment programs, "high-yield financial programs," or issue to countries or to outside parties an "IMF Number," "IMF Country Registration Number," or an "IMF Approval Number for Projects."

Other examples of bogus instruments often featured in such schemes which unauthorizedly use the name of the IMF are:

* fictitious stand-by letters of credit--falsely portrayed as risk-free and sanctioned by the IMF;

* securities allegedly backed by the IMF; and

* bonds supposedly issued by the IMF.

The IMF is an intergovernmental organization whose financial transactions and operations are carried out directly with its member countries and only through a fiscal agency designated by each member for this purpose (such as the member's Central Bank or its Ministry of Finance). The IMF does not operate through other agents and it does not endorse the activities of any bank, financial institution, or other public or private agency.

Other examples of bogus instruments often featured in such schemes which unauthorizedly use the name of the IMF are:

* fictitious stand-by letters of credit--falsely portrayed as risk-free and sanctioned by the IMF;

* securities allegedly backed by the IMF; and

* bonds supposedly issued by the IMF.

The IMF is an intergovernmental organization whose financial transactions and operations are carried out directly with its member countries and only through a fiscal agency designated by each member for this purpose (such as the member's Central Bank or its Ministry of Finance). The IMF does not operate through other agents and it does not endorse the activities of any bank, financial institution, or other public or private agency.

Standby Letters of Credit: The Private Primary Market

Designed to provide much of the information required for conducting a due diligence investigation.

Lender/Investors are skeptical of opportunities that offer above-market returns. If significant capital is required, little information is readily available with which to conduct a due diligence investigation, there is little motivation for committing funds.

Issues Covered

* A letter from the Securities and Exchange Commission, (S.E.C) stating that letters of credit are exempt from registration under the Securities Act of 1933.

* An opinion from the U.S Supreme Court stating that letters of credit, when acquired for cash, are the equivalent of a deposit liability.

* A legal historical example of a clean standby letter of credit, the text of which is clean of any requirements of documentation of nonperformance or default for the beneficiary to obtain payment.

* A discussion of the role of the International Chamber of Commerce in encouraging more equitable practices in the area of standby letters of credit.

* A discussion of case law and legal writing showing that pertaining law has developed away from domestic concepts and structures, and that it is a fallacy to think in terms of a comprehensive body of domestic law on LOC and especially in terms of diversity of national laws.

* A discussion of transmission, authenticity and the operative instrument; how it is determined when a transmission is authentic and legal.

* The issuance of standby LOC involves the separation of many of the services associated with lending, such as credit risk evaluation and underwriting, from funding.

* Banks argue that they are in the risk management business - whether on or off the balance sheet.

* An important difference between a standby LOC and conventional financing with uninsured depositors is that a standby LOC beneficiary retains the loan in the event of bank failure as opposed to having to stand in line with the FDIC and other creditors to recover the remaining assets of the bank.

* The greatest motivation for off-balance sheet banking is the opportunity cost of funding assets with reservable deposits without a binding capital constraint.

* In issuing an off-balance sheet instrument, the bank acts as a third party in a commercial transaction, substituting the bank's credit worthiness for that of its customer to facilitate exchange while sharing some of its risk with the lender/investor.

* In effect, banks are willing to rent their credit standing or borrow credit analysis to lender/investors by guaranteeing the payment of principal and interest-which may be of value to a bank customer who is not well known or established. This enables a bank to receive an underwriting fee that can bolster current profits without tieing up capital.

* A bank may not be asked to issue a guarantee unless it is perceived by the market to be strong.

* How a standby LOC is similar to an uninsured deposit and subordinated note in that it's value varies inversely with the credit risk of the bank.

* The incentive to the lender/investor? The return on this arrangement is likely to be greater than that of a deposit while still maintaining insurance against loss.

* The types of entities who acquire standby LOC.

* A discussion of repurchase programs and credit-enhanced loan transactions.

EVERY STATEMENT IN THESE REFERENCES EITHER A LEGAL PRECEDENT, REPORT OR LETTER ISSUED BY A GOVERNMENT AGENCY, TRADE PUBLICATION OR KNOWN ENTITY IN BANKING AND FINANCE.

Lender/Investors are skeptical of opportunities that offer above-market returns. If significant capital is required, little information is readily available with which to conduct a due diligence investigation, there is little motivation for committing funds.

Issues Covered

* A letter from the Securities and Exchange Commission, (S.E.C) stating that letters of credit are exempt from registration under the Securities Act of 1933.

* An opinion from the U.S Supreme Court stating that letters of credit, when acquired for cash, are the equivalent of a deposit liability.

* A legal historical example of a clean standby letter of credit, the text of which is clean of any requirements of documentation of nonperformance or default for the beneficiary to obtain payment.

* A discussion of the role of the International Chamber of Commerce in encouraging more equitable practices in the area of standby letters of credit.

* A discussion of case law and legal writing showing that pertaining law has developed away from domestic concepts and structures, and that it is a fallacy to think in terms of a comprehensive body of domestic law on LOC and especially in terms of diversity of national laws.

* A discussion of transmission, authenticity and the operative instrument; how it is determined when a transmission is authentic and legal.

* The issuance of standby LOC involves the separation of many of the services associated with lending, such as credit risk evaluation and underwriting, from funding.

* Banks argue that they are in the risk management business - whether on or off the balance sheet.

* An important difference between a standby LOC and conventional financing with uninsured depositors is that a standby LOC beneficiary retains the loan in the event of bank failure as opposed to having to stand in line with the FDIC and other creditors to recover the remaining assets of the bank.

* The greatest motivation for off-balance sheet banking is the opportunity cost of funding assets with reservable deposits without a binding capital constraint.

* In issuing an off-balance sheet instrument, the bank acts as a third party in a commercial transaction, substituting the bank's credit worthiness for that of its customer to facilitate exchange while sharing some of its risk with the lender/investor.

* In effect, banks are willing to rent their credit standing or borrow credit analysis to lender/investors by guaranteeing the payment of principal and interest-which may be of value to a bank customer who is not well known or established. This enables a bank to receive an underwriting fee that can bolster current profits without tieing up capital.

* A bank may not be asked to issue a guarantee unless it is perceived by the market to be strong.

* How a standby LOC is similar to an uninsured deposit and subordinated note in that it's value varies inversely with the credit risk of the bank.

* The incentive to the lender/investor? The return on this arrangement is likely to be greater than that of a deposit while still maintaining insurance against loss.

* The types of entities who acquire standby LOC.

* A discussion of repurchase programs and credit-enhanced loan transactions.

EVERY STATEMENT IN THESE REFERENCES EITHER A LEGAL PRECEDENT, REPORT OR LETTER ISSUED BY A GOVERNMENT AGENCY, TRADE PUBLICATION OR KNOWN ENTITY IN BANKING AND FINANCE.

The Prime Bank Instrument Raises Its (Ugly) Head Again

May 8, 1998 - The Vancouver Sun newspaper ran a story about a couple who lost $70,000 Canadian in a prime bank instrument program. Their's is not an isolated case.

Selling the sizzle is what these fraudsters are good at, and the good ones ply their trade with all the finesse and confidence of Wall Street promoters. The prime bank note or bank roll program has been around for years, but like the Nigerian Scam, it continues to catch new victims. According to the International Chamber of Commerce's commercial crime bureau, it involves $10 million US daily in North America alone.

The Sun story explained how Bob and Robin Blanchard borrowed the money to invest in the program in 1995 after signing a non-disclosure statement to prevent them from talking about the deal with anyone, including lawyers, financial advisors because they were joining " a priviledged group getting in on a very exclusive investment" which relies on secrecy.

What makes gives the scam it's allure is the idea that those who partake are joining an elite group of investors with access to extremely valuable and highly confidential information. Although there are a number of variations, the principle is the same. The big banks around the world lend each other money by issuing notes with face values of $100 million or more. These notes can be re-sold number of times at a discount (profit) to other lenders so that the original issuer can reap a handsome profit in a relatively short time. The figure commonly bandied about is 30% per month. The term of the notes vary from 30 days to a year or more.

Small investors must pool their money to build it up to a minimum $10 to $100 million so brokers get involved. Often a tax haven country is used to add to the intrigue and no tax need be paid by the shrewd investor, or at least that is what they are told.

To make the story more believeable, the names of large, well-known international banks like Barclays, Lloyds Bank and Chase Manhatten are used.

To the scrupulous investor there are some danger signals that should tip you off.

1. You are told as an investor and not a principle (you don't have $10 million US) you have no personal security. The broker will tell you that there is no need to worry because every penny is secured by an LC (Letter of Credit) or other guaranteed bank certificate.

2. You are told not to phone the bank who's name you are given because they cannot acknowledge the existence of such an arrangement unless you are the principle.

3. There is a high degree of trust necessary. The broker will tell you that he has no interest in stealing your money because he makes enough from the deal already, and besides, he wants to have you participate in the next program so you and he can get rich together.

4. You are told not to seek professional advice because the information is reserved only for those who participate in the program. Strangely few if any lawyers or professional advisors are invited into the program.

Often exotic sounding banking terms are bandied around that are confusing to all but the professional banker or investor. This is done to intentionally confuse and intimidate the victim so that they feel too self-conscious to ask questions. You might even be shown what appear to be high quality documents purporting to be from genuine lending institutions but there is no way to check their authenticity. Usually they are either worthless or forged.

The sad part is that the victim may not fully appreciate their true fate until years later. The brokers will keep the dream alive by saying that the profits have been re-invested and may even attempt to lure the victim into another scheme before they realize what they are into.

Selling the sizzle is what these fraudsters are good at, and the good ones ply their trade with all the finesse and confidence of Wall Street promoters. The prime bank note or bank roll program has been around for years, but like the Nigerian Scam, it continues to catch new victims. According to the International Chamber of Commerce's commercial crime bureau, it involves $10 million US daily in North America alone.

The Sun story explained how Bob and Robin Blanchard borrowed the money to invest in the program in 1995 after signing a non-disclosure statement to prevent them from talking about the deal with anyone, including lawyers, financial advisors because they were joining " a priviledged group getting in on a very exclusive investment" which relies on secrecy.

What makes gives the scam it's allure is the idea that those who partake are joining an elite group of investors with access to extremely valuable and highly confidential information. Although there are a number of variations, the principle is the same. The big banks around the world lend each other money by issuing notes with face values of $100 million or more. These notes can be re-sold number of times at a discount (profit) to other lenders so that the original issuer can reap a handsome profit in a relatively short time. The figure commonly bandied about is 30% per month. The term of the notes vary from 30 days to a year or more.

Small investors must pool their money to build it up to a minimum $10 to $100 million so brokers get involved. Often a tax haven country is used to add to the intrigue and no tax need be paid by the shrewd investor, or at least that is what they are told.

To make the story more believeable, the names of large, well-known international banks like Barclays, Lloyds Bank and Chase Manhatten are used.

To the scrupulous investor there are some danger signals that should tip you off.

1. You are told as an investor and not a principle (you don't have $10 million US) you have no personal security. The broker will tell you that there is no need to worry because every penny is secured by an LC (Letter of Credit) or other guaranteed bank certificate.

2. You are told not to phone the bank who's name you are given because they cannot acknowledge the existence of such an arrangement unless you are the principle.

3. There is a high degree of trust necessary. The broker will tell you that he has no interest in stealing your money because he makes enough from the deal already, and besides, he wants to have you participate in the next program so you and he can get rich together.

4. You are told not to seek professional advice because the information is reserved only for those who participate in the program. Strangely few if any lawyers or professional advisors are invited into the program.

Often exotic sounding banking terms are bandied around that are confusing to all but the professional banker or investor. This is done to intentionally confuse and intimidate the victim so that they feel too self-conscious to ask questions. You might even be shown what appear to be high quality documents purporting to be from genuine lending institutions but there is no way to check their authenticity. Usually they are either worthless or forged.

The sad part is that the victim may not fully appreciate their true fate until years later. The brokers will keep the dream alive by saying that the profits have been re-invested and may even attempt to lure the victim into another scheme before they realize what they are into.

So-called "Prime" Bank and Similar Financial Instruments

The Securities and Exchange Commission is alerting investors to the recent rise in possibly fraudulent schemes involving the issuance, trading or use of so-called "prime" bank, "prime" European bank or "prime" world bank financial instruments. These instruments typically take the form of notes, debentures, letters of credit, and guarantees. Also typical in the offer of these instruments is the promise or guarantee of unrealistic rates of return, for example, a 150 percent annualized rate of "profits." Common targets of these schemes include both institutional and individual investors, who may also be induced to participate in possible "Ponzi" schemes involving the pooling of investors' funds to purchase "prime" bank financial instruments.

On October 21, 1993, federal financial institution supervisory agencies issued an Interagency Advisory to their regulated financial institutions. The Interagency Advisory warned of the use of schemes involving "prime" bank financial instruments and noted that:

* Individuals have been improperly using the names of large, well-known domestic and foreign banks, the World Bank, and central banks in connection with their "Prime Bank" schemes.

* The named institutions "had no knowledge about the unauthorized use of their names or the issuance or anything akin to 'Prime Bank'-type financial instruments."

* The staffs of the federal supervisory agencies are unaware of the legitimate use of any financial instrument called a "Prime Bank" note, guarantee, letter of credit, debenture, or similar type of financial instrument.

* Financial institutions should watch for the attempted use of traditional types of financial instruments that are referred to in an unconventional manner, "such as a letter of credit referencing forms allegedly produced or approved by the International Chamber of Commerce."

As to this latter point, the Interagency Advisory referred to examples of "bogus schemes involving the supposed issuance of an 'ICC 3034' or an 'ICC 3039' letter of credit by a domestic or foreign bank."

The Interagency Advisory also noted that many of the illegal or dubious schemes "appear to involve overly complex loan funding.

These schemes do not involve the offer or sale of financial instruments issued by any financial institution having the word "prime" in its name; rather, that word (or a synonym, as in the phrase "top fifty world banks") is used to refer, generically, to financial institutions of purportedly high repute and financial soundness. These agencies are the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, the National Credit Union Administration, the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, and the Office of Thrift Supervision.

In the eyes of an unsophisticated investor, this complexity may make a questionable investment appear worthwhile. The SEC warns investors and those who may advise them, particularly broker-dealers and investment advisors, of this possible hallmark of fraud and reminds them of a basic rule for avoiding securities fraud, "If it looks too good to be true, it probably is!"

On October 21, 1993, federal financial institution supervisory agencies issued an Interagency Advisory to their regulated financial institutions. The Interagency Advisory warned of the use of schemes involving "prime" bank financial instruments and noted that:

* Individuals have been improperly using the names of large, well-known domestic and foreign banks, the World Bank, and central banks in connection with their "Prime Bank" schemes.

* The named institutions "had no knowledge about the unauthorized use of their names or the issuance or anything akin to 'Prime Bank'-type financial instruments."

* The staffs of the federal supervisory agencies are unaware of the legitimate use of any financial instrument called a "Prime Bank" note, guarantee, letter of credit, debenture, or similar type of financial instrument.

* Financial institutions should watch for the attempted use of traditional types of financial instruments that are referred to in an unconventional manner, "such as a letter of credit referencing forms allegedly produced or approved by the International Chamber of Commerce."

As to this latter point, the Interagency Advisory referred to examples of "bogus schemes involving the supposed issuance of an 'ICC 3034' or an 'ICC 3039' letter of credit by a domestic or foreign bank."

The Interagency Advisory also noted that many of the illegal or dubious schemes "appear to involve overly complex loan funding.

These schemes do not involve the offer or sale of financial instruments issued by any financial institution having the word "prime" in its name; rather, that word (or a synonym, as in the phrase "top fifty world banks") is used to refer, generically, to financial institutions of purportedly high repute and financial soundness. These agencies are the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, the National Credit Union Administration, the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, and the Office of Thrift Supervision.

In the eyes of an unsophisticated investor, this complexity may make a questionable investment appear worthwhile. The SEC warns investors and those who may advise them, particularly broker-dealers and investment advisors, of this possible hallmark of fraud and reminds them of a basic rule for avoiding securities fraud, "If it looks too good to be true, it probably is!"

Paper Trading

What percentage of new clients paper trade before actually risking real money in the futures markets?

Not surprisingly a lot of new traders get their feet wet by first taking trades on paper and recording theoretical results. Probably half of all new traders that we work with take this approach in the beginning. Often though, success on paper looks easy and these traders are tempted to risk real dollars before they have really had their confidence tested.

Before their confidence has been tested? In your opinion what's a reasonable amount of time for someone to get this sort of confidence?

Trading on paper can be deceptive, and after a few profitable trades in a row (on paper), people tend to feel like they are missing out by not having actual dollars in the market(s). Unfortunately a really important part of being a good trader has to do with keeping your perspective when you go through losing periods, which are inevitable. Unless you have seen yourself and your trading methods go through a number of these profit/loss cycles, it is hard to have this perspective.

For most people, it is probably a good idea to paper trade for at least 3-6 months before risking real money. Some people get bored with this, of course, and simply choose to “pay their tuition up front.” This trial-by-fire approach will help hold your interest, but obviously, it can be expensive.

Not surprisingly a lot of new traders get their feet wet by first taking trades on paper and recording theoretical results. Probably half of all new traders that we work with take this approach in the beginning. Often though, success on paper looks easy and these traders are tempted to risk real dollars before they have really had their confidence tested.

Before their confidence has been tested? In your opinion what's a reasonable amount of time for someone to get this sort of confidence?

Trading on paper can be deceptive, and after a few profitable trades in a row (on paper), people tend to feel like they are missing out by not having actual dollars in the market(s). Unfortunately a really important part of being a good trader has to do with keeping your perspective when you go through losing periods, which are inevitable. Unless you have seen yourself and your trading methods go through a number of these profit/loss cycles, it is hard to have this perspective.

For most people, it is probably a good idea to paper trade for at least 3-6 months before risking real money. Some people get bored with this, of course, and simply choose to “pay their tuition up front.” This trial-by-fire approach will help hold your interest, but obviously, it can be expensive.

The International Bank Debenture Trading

Introduction

The following document has been prepared based upon all the available information and is largely a hypotheses, due to the fact that much of the information is hearsay and unsubstantiated. The basis in fact, however, is strong and several documents which re attached as appendices give a detailed summary of the information and reasoning behind this document.

Basic history of specific types of credit instruments

The issuance of bank (credit) instruments dates back to the early days of "banking" when private wealthy individuals used their capital to support various trade orientated ventures. Promissory Notes, Bills of Exchange, Bankers Acceptances and Letters of Credit have all been a part of daily "bank" business for many years.

There are three types of Letters of Credit which are issued on a daily basis. These are Documentary Letters of Credit, Standby Letters of Credit and Unconditional Letters of Credit or Surety Guarantees.

The issuance of a "Letter of Credit" usually takes place when a bank customer (Buyer) wishes to buy or acquire goods or services from a third party (Seller). The Buyer will cause his bank to issue a Letter of Credit which "guarantees" payment to the Seller via the Seller's bank conditional against certain documentary requirements. In other words, when the Seller via his bank represents certain documents to the Buyer's bank the payment will be made. These documentary requirements vary from transaction to transaction, however, the normal type of documents will usually comprise of:

- Invoice from Seller (usually in triplicate)

- Bill of Lading (from Shipper)

- certificate of Origin (from the Seller)

- Insurance documents (to cover goods in transit)

- Export Certificate (if goods are for export)

- Transfer of Ownership (from the Seller)

These documents effectively "guarantee" that the goods were "sold" and are "en route" to the Buyer. The Buyer is secure in the fact that he has "bought" the items or services and the Seller is secure in the fact that the Letter of Credit, which was delivered to him prior to the loading or release of the goods, will "guarantee" payment if he complies with the terms of the Letter of Credit.

This type of transaction takes place every day throughout the world, in every jurisdiction and without any fear that the issuing bank will not "honour" its obligation, providing that the bank if of an acceptable stature.

The Letter of Credit is issued i a manner which has been recognised by the Bank for International Settlements (B.I.S.) and the International Chamber of Commerce (I.C.C), and is subject to the uniform rules of collection for documentary credits (ICC 400, 1983).

This type of instrument is normally called a Documentary Letter of Credit ("DLC") and is always trade or transaction related, with an underlying sale of goods or services between the applicant (Buyer) and the Beneficiary (Seller).

During the evolution of the trade related Letters of Credit, a number of institutions began to issue Standby Letters of Credit )"SLC's"). These credit instruments were effectively a surety or guarantee that if the applicant (Buyer) failed to pay or perform under the terms of a transaction, the bank would take over the liability and pay the beneficiary (Seller).

In the United States banks are prohibited by regulation from providing formal guarantees and instead offer these instruments as a functional equivalent of a guarantee.

A conventional Standby Letter of Credit (CSLC) is an irrevocable obligation in the form of a Letter of Credit issued by a bank on behalf of its customer. If the bank's customer is unable to meet the terms and conditions of its contractual agreement with a third party, the issuing bank is obligated to pay the third party (as stipulated in the terms of the CSLC) on behalf of its customer. A CSLC can be primary (direct draw on the Bank) or secondary (available in the event of default by the customer to pay the underlying obligation). [Extracts from "recent Innovations in International Banking - April 1986 prepared by a study group established by the Central Banks of the Group of Ten Countries and published by the Bank for International Settlements.]

As these Standby Letters of Credit were effectively contingent liabilities based upon the potential formal default or technical default of the applicant, they are held "off balance" sheet in respect to the bank's accounting principles.

This type of Letter of Credit is commonly referred to in the market place as a short form format. This number is not found as a specific ICC 400 (1983) reference and is purported to be a federal court docket reference number which is related to a law suit involving such instrument, no details are available to the author.

The following document has been prepared based upon all the available information and is largely a hypotheses, due to the fact that much of the information is hearsay and unsubstantiated. The basis in fact, however, is strong and several documents which re attached as appendices give a detailed summary of the information and reasoning behind this document.

Basic history of specific types of credit instruments

The issuance of bank (credit) instruments dates back to the early days of "banking" when private wealthy individuals used their capital to support various trade orientated ventures. Promissory Notes, Bills of Exchange, Bankers Acceptances and Letters of Credit have all been a part of daily "bank" business for many years.

There are three types of Letters of Credit which are issued on a daily basis. These are Documentary Letters of Credit, Standby Letters of Credit and Unconditional Letters of Credit or Surety Guarantees.

The issuance of a "Letter of Credit" usually takes place when a bank customer (Buyer) wishes to buy or acquire goods or services from a third party (Seller). The Buyer will cause his bank to issue a Letter of Credit which "guarantees" payment to the Seller via the Seller's bank conditional against certain documentary requirements. In other words, when the Seller via his bank represents certain documents to the Buyer's bank the payment will be made. These documentary requirements vary from transaction to transaction, however, the normal type of documents will usually comprise of:

- Invoice from Seller (usually in triplicate)

- Bill of Lading (from Shipper)

- certificate of Origin (from the Seller)

- Insurance documents (to cover goods in transit)

- Export Certificate (if goods are for export)

- Transfer of Ownership (from the Seller)

These documents effectively "guarantee" that the goods were "sold" and are "en route" to the Buyer. The Buyer is secure in the fact that he has "bought" the items or services and the Seller is secure in the fact that the Letter of Credit, which was delivered to him prior to the loading or release of the goods, will "guarantee" payment if he complies with the terms of the Letter of Credit.

This type of transaction takes place every day throughout the world, in every jurisdiction and without any fear that the issuing bank will not "honour" its obligation, providing that the bank if of an acceptable stature.

The Letter of Credit is issued i a manner which has been recognised by the Bank for International Settlements (B.I.S.) and the International Chamber of Commerce (I.C.C), and is subject to the uniform rules of collection for documentary credits (ICC 400, 1983).

This type of instrument is normally called a Documentary Letter of Credit ("DLC") and is always trade or transaction related, with an underlying sale of goods or services between the applicant (Buyer) and the Beneficiary (Seller).

During the evolution of the trade related Letters of Credit, a number of institutions began to issue Standby Letters of Credit )"SLC's"). These credit instruments were effectively a surety or guarantee that if the applicant (Buyer) failed to pay or perform under the terms of a transaction, the bank would take over the liability and pay the beneficiary (Seller).

In the United States banks are prohibited by regulation from providing formal guarantees and instead offer these instruments as a functional equivalent of a guarantee.

A conventional Standby Letter of Credit (CSLC) is an irrevocable obligation in the form of a Letter of Credit issued by a bank on behalf of its customer. If the bank's customer is unable to meet the terms and conditions of its contractual agreement with a third party, the issuing bank is obligated to pay the third party (as stipulated in the terms of the CSLC) on behalf of its customer. A CSLC can be primary (direct draw on the Bank) or secondary (available in the event of default by the customer to pay the underlying obligation). [Extracts from "recent Innovations in International Banking - April 1986 prepared by a study group established by the Central Banks of the Group of Ten Countries and published by the Bank for International Settlements.]

As these Standby Letters of Credit were effectively contingent liabilities based upon the potential formal default or technical default of the applicant, they are held "off balance" sheet in respect to the bank's accounting principles.

This type of Letter of Credit is commonly referred to in the market place as a short form format. This number is not found as a specific ICC 400 (1983) reference and is purported to be a federal court docket reference number which is related to a law suit involving such instrument, no details are available to the author.

Wednesday, June 2, 2010

Trade Execution: What Every Investor Should Know

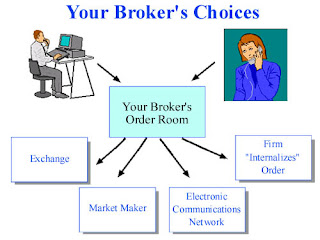

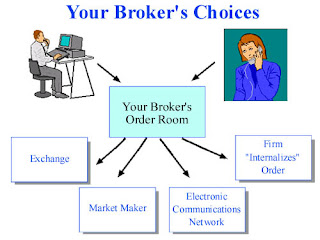

The graphic below shows your broker's options for executing your trade:

Your Broker Has a Duty of “Best Execution”

Many firms use automated systems to handle the orders they receive from their customers. In deciding how to execute orders, your broker has a duty to seek the best execution that is reasonably available for its customers' orders. That means your broker must evaluate the orders it receives from all customers in the aggregate and periodically assess which competing markets, market makers, or ECNs offer the most favorable terms of execution.

The opportunity for "price improvement" – which is the opportunity, but not the guarantee, for an order to be executed at a better price than what is currently quoted publicly – is an important factor a broker should consider in executing its customers' orders. Other factors include the speed and the likelihood of execution.

Here's an example of how price improvement can work: Let's say you enter a market order to sell 500 shares of a stock. The current quote is $20. Your broker may be able to send your order to a market or a market maker where your order would have the possibility of getting a price better than $20. If your order is executed at $20 1/16, you would receive $10,031.25 for the sale of your stock – $31.25 more than if your broker had only been able to get the current quote for you.

Of course, the additional time it takes some markets to execute orders may result in your getting a worse price than the current quote – especially in a fast-moving market. So, your broker is required to consider whether there is a trade-off between providing its customers' orders with the possibility – but not the guarantee – of better prices and the extra time it may take to do so.

You Have Options for Directing Trades

If for any reason you want to direct your trade to a particular exchange, market maker, or ECN, you may be able to call your broker and ask him or her to do this. But some brokers may charge for that service. Some brokers now offer active traders the ability to direct orders in Nasdaq stocks to the market maker or ECN of their choice.

In a recent speech, SEC Chairman Arthur Levitt emphasized that investors have the right to know where and how their firms execute their orders and what steps they take to assure best execution.

Ask your broker about the firm's policies on payment for order flow, internalization, or other routing practices – or look for that information in your new account agreement. You can also write to your broker to find out the nature and source of any payment for order flow it may have received for a particular order.

If you're comparing firms, ask each how often it gets price improvement on customers' orders. And then consider that information in deciding with which firm you will do business.

Your Broker Has a Duty of “Best Execution”

Many firms use automated systems to handle the orders they receive from their customers. In deciding how to execute orders, your broker has a duty to seek the best execution that is reasonably available for its customers' orders. That means your broker must evaluate the orders it receives from all customers in the aggregate and periodically assess which competing markets, market makers, or ECNs offer the most favorable terms of execution.

The opportunity for "price improvement" – which is the opportunity, but not the guarantee, for an order to be executed at a better price than what is currently quoted publicly – is an important factor a broker should consider in executing its customers' orders. Other factors include the speed and the likelihood of execution.

Here's an example of how price improvement can work: Let's say you enter a market order to sell 500 shares of a stock. The current quote is $20. Your broker may be able to send your order to a market or a market maker where your order would have the possibility of getting a price better than $20. If your order is executed at $20 1/16, you would receive $10,031.25 for the sale of your stock – $31.25 more than if your broker had only been able to get the current quote for you.

Of course, the additional time it takes some markets to execute orders may result in your getting a worse price than the current quote – especially in a fast-moving market. So, your broker is required to consider whether there is a trade-off between providing its customers' orders with the possibility – but not the guarantee – of better prices and the extra time it may take to do so.

You Have Options for Directing Trades

If for any reason you want to direct your trade to a particular exchange, market maker, or ECN, you may be able to call your broker and ask him or her to do this. But some brokers may charge for that service. Some brokers now offer active traders the ability to direct orders in Nasdaq stocks to the market maker or ECN of their choice.

In a recent speech, SEC Chairman Arthur Levitt emphasized that investors have the right to know where and how their firms execute their orders and what steps they take to assure best execution.

Ask your broker about the firm's policies on payment for order flow, internalization, or other routing practices – or look for that information in your new account agreement. You can also write to your broker to find out the nature and source of any payment for order flow it may have received for a particular order.

If you're comparing firms, ask each how often it gets price improvement on customers' orders. And then consider that information in deciding with which firm you will do business.

Trade Execution: What Every Investor Should Know (continue.....)

When you place an order to buy or sell stock, you might not think about where or how your broker will execute the trade. But where and how your order is executed can impact the overall costs of the transaction, including the price you pay for the stock. Here's what you should know about trade execution:

Trade Execution Isn’t Instantaneous

Many investors who trade through online brokerage accounts assume they have a direct connection to the securities markets. But they don't. When you push that enter key, your order is sent over the Internet to your broker—who in turn decides which market to send it to for execution. A similar process occurs when you call your broker to place a trade.

While trade execution is usually seamless and quick, it does take time. And prices can change quickly, especially in fast-moving markets. Because price quotes are only for a specific number of shares, investors may not always receive the price they saw on their screen or the price their broker quoted over the phone. By the time your order reaches the market, the price of the stock could be slightly – or very – different.

No SEC regulations require a trade to be executed within a set period of time. But if firms advertise their speed of execution, they must not exaggerate or fail to tell investors about the possibility of significant delays.

Your Broker Has Options for Executing Your Trade

Just as you have a choice of brokers, your broker generally has a choice of markets to execute your trade:

* For a stock that is listed on an exchange, such as the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE), your broker may direct the order to that exchange, to another exchange (such as a regional exchange), or to a firm called a "third market maker." A "third market maker" is a firm that stands ready to buy or sell a stock listed on an exchange at publicly quoted prices. As a way to attract orders from brokers, some regional exchanges or third market makers will pay your broker for routing your order to that exchange or market maker—perhaps a penny or more per share for your order. This is called "payment for order flow."

* For a stock that trades in an over-the-counter (OTC) market, such as the Nasdaq, your broker may send the order to a "Nasdaq market maker" in the stock. Many Nasdaq market makers also pay brokers for order flow.

* Your broker may route your order – especially a "limit order" – to an electronic communications network (ECN) that automatically matches buy and sell orders at specified prices. A "limit order" is an order to buy or sell a stock at a specific price.

* Your broker may decide to send your order to another division of your broker's firm to be filled out of the firm's own inventory. This is called "internalization". In this way, your broker's firm may make money on the "spread" – which is the difference between the purchase price and the sale price.

Trade Execution Isn’t Instantaneous

Many investors who trade through online brokerage accounts assume they have a direct connection to the securities markets. But they don't. When you push that enter key, your order is sent over the Internet to your broker—who in turn decides which market to send it to for execution. A similar process occurs when you call your broker to place a trade.

While trade execution is usually seamless and quick, it does take time. And prices can change quickly, especially in fast-moving markets. Because price quotes are only for a specific number of shares, investors may not always receive the price they saw on their screen or the price their broker quoted over the phone. By the time your order reaches the market, the price of the stock could be slightly – or very – different.

No SEC regulations require a trade to be executed within a set period of time. But if firms advertise their speed of execution, they must not exaggerate or fail to tell investors about the possibility of significant delays.

Your Broker Has Options for Executing Your Trade

Just as you have a choice of brokers, your broker generally has a choice of markets to execute your trade:

* For a stock that is listed on an exchange, such as the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE), your broker may direct the order to that exchange, to another exchange (such as a regional exchange), or to a firm called a "third market maker." A "third market maker" is a firm that stands ready to buy or sell a stock listed on an exchange at publicly quoted prices. As a way to attract orders from brokers, some regional exchanges or third market makers will pay your broker for routing your order to that exchange or market maker—perhaps a penny or more per share for your order. This is called "payment for order flow."

* For a stock that trades in an over-the-counter (OTC) market, such as the Nasdaq, your broker may send the order to a "Nasdaq market maker" in the stock. Many Nasdaq market makers also pay brokers for order flow.

* Your broker may route your order – especially a "limit order" – to an electronic communications network (ECN) that automatically matches buy and sell orders at specified prices. A "limit order" is an order to buy or sell a stock at a specific price.

* Your broker may decide to send your order to another division of your broker's firm to be filled out of the firm's own inventory. This is called "internalization". In this way, your broker's firm may make money on the "spread" – which is the difference between the purchase price and the sale price.

About Settling Trades In Three Days: Introducing T+3

Beginning on June 7, 1995, investors must settle their security transactions in three business days rather than five. This shortened settlement cycle is known as "T+3" - shorthand for "trade date plus three days."

This new rule means that when you buy securities, your payment must be received by your brokerage firm no later than three business days after the trade is executed. And if you sell securities, your brokerage firm must receive your securities certificate no later than three business days after you authorized the sale.

The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission developed this brochure to address frequently asked questions about why the settlement cycle was shortened and to highlight issues you should consider in preparing for three-day settlement.

"Why the change?"

Unsettled trades pose risks to our financial markets, especially when market prices plunge and trading volumes soar. This happened when the stock market fell by over 500 points on October 19, 1987. In the hours and days following this drop, our financial markets were threatened by doubts about whether securities firms and investors hit by sizable losses would be able to pay for their transactions. By reducing the settlement cycle from five to three business days, the SEC has lessened the amount of money that needs to be collected at any one time, and strengthened our financial markets for times of stress.

"What security transactions are covered?"

Most security transactions, including stocks, bonds, municipal securities, mutual funds traded through a broker, and limited partnerships that trade on an exchange, must settle in three days. Government securities and options will continue to settle as they have in the past - one day following a purchase or sale.

This new rule means that when you buy securities, your payment must be received by your brokerage firm no later than three business days after the trade is executed. And if you sell securities, your brokerage firm must receive your securities certificate no later than three business days after you authorized the sale.

The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission developed this brochure to address frequently asked questions about why the settlement cycle was shortened and to highlight issues you should consider in preparing for three-day settlement.

"Why the change?"

Unsettled trades pose risks to our financial markets, especially when market prices plunge and trading volumes soar. This happened when the stock market fell by over 500 points on October 19, 1987. In the hours and days following this drop, our financial markets were threatened by doubts about whether securities firms and investors hit by sizable losses would be able to pay for their transactions. By reducing the settlement cycle from five to three business days, the SEC has lessened the amount of money that needs to be collected at any one time, and strengthened our financial markets for times of stress.

"What security transactions are covered?"

Most security transactions, including stocks, bonds, municipal securities, mutual funds traded through a broker, and limited partnerships that trade on an exchange, must settle in three days. Government securities and options will continue to settle as they have in the past - one day following a purchase or sale.

Tips for Online Investing: What You Need to Know About Trading In Fast-Moving Markets

The price of some stocks, especially recent "hot" IPOs and high tech stocks, can soar and drop suddenly. In these fast markets when many investors want to trade at the same time and prices change quickly, delays can develop across the board. Executions and confirmations slow down, while reports of prices lag behind actual prices. In these markets, investors can suffer unexpected losses very quickly.

Investors trading over the Internet or online, who are used to instant access to their accounts and near instantaneous executions of their trades, especially need to understand how they can protect themselves in fast-moving markets.

You can limit your losses in fast-moving markets if you

* know what you are buying and the risks of your investment; and

* know how trading changes during fast markets and take additional steps to guard against the typical problems investors face in these markets.

Online trading is quick and easy, online investing takes time

With a click of mouse, you can buy and sell stocks from more than 100 online brokers offering executions as low as $5 per transaction. Although online trading saves investors time and money, it does not take the homework out of making investment decisions. You may be able to make a trade in a nanosecond, but making wise investment decisions takes time. Before you trade, know why you are buying or selling, and the risk of your investment.

Investors trading over the Internet or online, who are used to instant access to their accounts and near instantaneous executions of their trades, especially need to understand how they can protect themselves in fast-moving markets.

You can limit your losses in fast-moving markets if you

* know what you are buying and the risks of your investment; and

* know how trading changes during fast markets and take additional steps to guard against the typical problems investors face in these markets.

Online trading is quick and easy, online investing takes time

With a click of mouse, you can buy and sell stocks from more than 100 online brokers offering executions as low as $5 per transaction. Although online trading saves investors time and money, it does not take the homework out of making investment decisions. You may be able to make a trade in a nanosecond, but making wise investment decisions takes time. Before you trade, know why you are buying or selling, and the risk of your investment.

Internet Fraud: How to Avoid Internet Investment Scams

Introduction

The Internet serves as an excellent tool for investors, allowing them to easily and inexpensively research investment opportunities. But the Internet is also an excellent tool for fraudsters. That's why you should always think twice before you invest your money in any opportunity you learn about through the Internet.

On October 28, 1998, the SEC announced charges against 44 stock promoters caught in a nationwide enforcement sweep to combat Internet fraud. These promoters failed to tell investors that more than 235 companies paid them millions of dollars in cash and shares in exchange for touting their stock on the Internet.

Not only did they lie about their own independence, some of them lied about the companies they featured, then took advantage of any quick spike in price to sell their shares for a fast and easy profit," said SEC Director of Enforcement Richard H. Walker.

This alert tells you how to spot different types of Internet fraud, what the SEC is doing to fight Internet investment scams, and how to use the Internet to invest wisely.

Navigating the Frontier: Where the Frauds Are

The Internet allows individuals or companies to communicate with a large audience without spending a lot of time, effort, or money. Anyone can reach tens of thousands of people by building an Internet web site, posting a message on an online bulletin board, entering a discussion in a live "chat" room, or sending mass e-mails. It's easy for fraudsters to make their messages look real and credible. But it's nearly impossible for investors to tell the difference between fact and fiction.

Online Investment Newsletters

Hundreds of online investment newsletters have appeared on the Internet in recent years. Many offer investors seemingly unbiased information free of charge about featured companies or recommending "stock picks of the month." While legitimate online newsletters can help investors gather valuable information, some online newsletters are tools for fraud.

Some companies pay the people who write online newsletters cash or securities to "tout" or recommend their stocks. While this isn't illegal, the federal securities laws require the newsletters to disclose who paid them, the amount, and the type of payment. But many fraudsters fail to do so. Instead, they'll lie about the payments they received, their independence, their so-called research, and their track records. Their newsletters masquerade as sources of unbiased information, when in fact they stand to profit handsomely if they convince investors to buy or sell particular stocks.

Some online newsletters falsely claim to independently research the stocks they profile. Others spread false information or promote worthless stocks. The most notorious sometimes "scalp" the stocks they hype, driving up the price of the stock with their baseless recommendations and then selling their own holdings at high prices and high profits. To learn how to separate the good from the bad, read our tips for checking out newsletters.

Bulletin Boards

Online bulletin boards – whether newsgroups, usenet, or web-based bulletin boards – have become an increasingly popular forum for investors to share information. Bulletin boards typically feature "threads" made up of numerous messages on various investment opportunities.

While some messages may be true, many turn out to be bogus – or even scams. Fraudsters often pump up a company or pretend to reveal "inside" information about upcoming announcements, new products, or lucrative contracts.

Also, you never know for certain who you're dealing with – or whether they're credible – because many bulletin boards allow users to hide their identity behind multiple aliases. People claiming to be unbiased observers who've carefully researched the company may actually be company insiders, large shareholders, or paid promoters. A single person can easily create the illusion of widespread interest in a small, thinly-traded stock by posting a series of messages under various aliases.

E-mail Spams

Because "spam" – junk e-mail – is so cheap and easy to create, fraudsters increasingly use it to find investors for bogus investment schemes or to spread false information about a company. Spam allows the unscrupulous to target many more potential investors than cold calling or mass mailing. Using a bulk e-mail program, spammers can send personalized messages to thousands and even millions of Internet users at a time.

How to Use the Internet to Invest Wisely

If you want to invest wisely and steer clear of frauds, you must get the facts. Never, ever, make an investment based solely on what you read in an online newsletter or bulletin board posting, especially if the investment involves a small, thinly-traded company that isn't well known.

The Internet serves as an excellent tool for investors, allowing them to easily and inexpensively research investment opportunities. But the Internet is also an excellent tool for fraudsters. That's why you should always think twice before you invest your money in any opportunity you learn about through the Internet.

On October 28, 1998, the SEC announced charges against 44 stock promoters caught in a nationwide enforcement sweep to combat Internet fraud. These promoters failed to tell investors that more than 235 companies paid them millions of dollars in cash and shares in exchange for touting their stock on the Internet.

Not only did they lie about their own independence, some of them lied about the companies they featured, then took advantage of any quick spike in price to sell their shares for a fast and easy profit," said SEC Director of Enforcement Richard H. Walker.

This alert tells you how to spot different types of Internet fraud, what the SEC is doing to fight Internet investment scams, and how to use the Internet to invest wisely.

Navigating the Frontier: Where the Frauds Are

The Internet allows individuals or companies to communicate with a large audience without spending a lot of time, effort, or money. Anyone can reach tens of thousands of people by building an Internet web site, posting a message on an online bulletin board, entering a discussion in a live "chat" room, or sending mass e-mails. It's easy for fraudsters to make their messages look real and credible. But it's nearly impossible for investors to tell the difference between fact and fiction.

Online Investment Newsletters

Hundreds of online investment newsletters have appeared on the Internet in recent years. Many offer investors seemingly unbiased information free of charge about featured companies or recommending "stock picks of the month." While legitimate online newsletters can help investors gather valuable information, some online newsletters are tools for fraud.

Some companies pay the people who write online newsletters cash or securities to "tout" or recommend their stocks. While this isn't illegal, the federal securities laws require the newsletters to disclose who paid them, the amount, and the type of payment. But many fraudsters fail to do so. Instead, they'll lie about the payments they received, their independence, their so-called research, and their track records. Their newsletters masquerade as sources of unbiased information, when in fact they stand to profit handsomely if they convince investors to buy or sell particular stocks.

Some online newsletters falsely claim to independently research the stocks they profile. Others spread false information or promote worthless stocks. The most notorious sometimes "scalp" the stocks they hype, driving up the price of the stock with their baseless recommendations and then selling their own holdings at high prices and high profits. To learn how to separate the good from the bad, read our tips for checking out newsletters.

Bulletin Boards

Online bulletin boards – whether newsgroups, usenet, or web-based bulletin boards – have become an increasingly popular forum for investors to share information. Bulletin boards typically feature "threads" made up of numerous messages on various investment opportunities.

While some messages may be true, many turn out to be bogus – or even scams. Fraudsters often pump up a company or pretend to reveal "inside" information about upcoming announcements, new products, or lucrative contracts.

Also, you never know for certain who you're dealing with – or whether they're credible – because many bulletin boards allow users to hide their identity behind multiple aliases. People claiming to be unbiased observers who've carefully researched the company may actually be company insiders, large shareholders, or paid promoters. A single person can easily create the illusion of widespread interest in a small, thinly-traded stock by posting a series of messages under various aliases.

E-mail Spams

Because "spam" – junk e-mail – is so cheap and easy to create, fraudsters increasingly use it to find investors for bogus investment schemes or to spread false information about a company. Spam allows the unscrupulous to target many more potential investors than cold calling or mass mailing. Using a bulk e-mail program, spammers can send personalized messages to thousands and even millions of Internet users at a time.

How to Use the Internet to Invest Wisely

If you want to invest wisely and steer clear of frauds, you must get the facts. Never, ever, make an investment based solely on what you read in an online newsletter or bulletin board posting, especially if the investment involves a small, thinly-traded company that isn't well known.

What are investment advisers?

What is an investment adviser?

Investment advisers are in the business of giving advice about securities to clients. For instance, if they receive compensation for giving advice to a specific person on investing in stocks, bonds, or mutual funds, they are investment advisers. Some investment advisers manage portfolios of securities.

What is the difference between an investment adviser and a financial planner?

Most financial planners are investment advisers, but not all investment advisers are financial planners. Some financial planners assess every aspect of your financial life-including saving, investments, insurance, taxes, retirement, and estate planning-and help you develop a detailed strategy or financial plan for meeting all your financial goals.

Others call themselves financial planners, but they may only be able to recommend that you invest in a narrow range of products, and sometimes products that aren't securities.

Before you hire any financial professional, you should know exactly what services you need, what services the professional can deliver, any limitations on what they can recommend, what services you're paying for, how much those services cost, and how the adviser or planner gets paid.

Investment advisers are in the business of giving advice about securities to clients. For instance, if they receive compensation for giving advice to a specific person on investing in stocks, bonds, or mutual funds, they are investment advisers. Some investment advisers manage portfolios of securities.

What is the difference between an investment adviser and a financial planner?

Most financial planners are investment advisers, but not all investment advisers are financial planners. Some financial planners assess every aspect of your financial life-including saving, investments, insurance, taxes, retirement, and estate planning-and help you develop a detailed strategy or financial plan for meeting all your financial goals.

Others call themselves financial planners, but they may only be able to recommend that you invest in a narrow range of products, and sometimes products that aren't securities.

Before you hire any financial professional, you should know exactly what services you need, what services the professional can deliver, any limitations on what they can recommend, what services you're paying for, how much those services cost, and how the adviser or planner gets paid.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)